Introduction to Writing a Persuasive Essay (Step-by-Step)

A strong persuasive essay changes minds! It presents a clear viewpoint, supports it with convincing reasons, and uses language techniques that nudge or guide the reader towards agreement.

This is useful for school, university, or professional writing. Mastering persuasive techniques will make your arguments more memorable and effective.

In this lesson prepared by Learn English Weekly, you’ll learn how to plan, structure, and refine a persuasive essay. We’ll cover the essentials: claims, reasons, evidence, and rhetorical devices. Then we'll finish with a full example essay you can model. Ready? Let's go!

What is a persuasive essay?

A persuasive essay aims to convince the reader to accept a viewpoint or take an action. Basically you want the reader to agree with your opinion! It overlaps with argumentative writing but places greater emphasis on rhetoric like tone, audience awareness, and stylistic devices, alongside logic and evidence.

Use our Dictionary

Don't know a word? Use our fun, free dictionary! Enter a word and you will see the meaning, pronunciation with an audio example, example sentence, and (hopefully) a great image to match!

Try for freeThe Core Structure (That Actually Persuades)

A simple, effective outline

- Introduction

- Hook to capture attention.

- Context to frame the issue.

- Thesis stating your position (what you want the reader to accept).

- Three body paragraphs

- Each paragraph = one reason supporting your position.

- Include evidence and reader-centred benefits.

- Counter-view + refutation

- Present the strongest objection, then disarm it.

- Conclusion

- Reaffirm your position and leave a clear call to action or implication.

Tip: Persuasion blends logic (logos), credibility (ethos), and emotion (pathos). Use all three, but never at the expense of accuracy.

Ideal word balance (for a 1,000–1,200-word essay)

- Introduction: 120–150 words

- Body (3 reasons): 600–720 words total

- Counter-view + refutation: 180–220 words

- Conclusion: 100–150 words

Planning with Audience in Mind

Pre-writing checklist

- Define your goal: What should the reader think or do after reading?

- Know your audience: What do they value? What might they resist?

- Craft a precise thesis: “This essay argues that X should happen because A, B, and C.”

- Select 2–3 compelling reasons: Prioritise reasons that benefit the reader.

- Gather evidence: Credible examples, data, expert views, real-world cases.

- Anticipate objections: Prepare concise, respectful refutations.

Writing the Essay

The Introduction — Hook, Bridge, Thesis

- Hook options: a surprising statistic, a vivid scenario, a short quotation, or a rhetorical question.

- Bridge: 1–2 lines linking the hook to your topic.

- Thesis: Clear, direct, and action-oriented.

Example thesis frames

- “This essay argues that schools should teach media literacy weekly, because it improves critical thinking, protects against misinformation, and enhances citizenship.”

- “It will be contended that cities should expand cycling infrastructure, as it reduces congestion, improves public health, and cuts emissions.”

Body Paragraphs — PERM method (Point → Evidence → Reasoning → Motive)

Use this to keep persuasion sharp and audience-focused:

- Point: Topic sentence with your reason.

- Evidence: Data, example, expert insight, or brief case.

- Reasoning: Explain how the evidence supports your point.

- Motive (reader benefit): Spell out why the reader should care.

Model

- Point: “Firstly, cycling lanes reduce congestion on key routes.”

- Evidence: Compare traffic flow figures or case studies.

- Reasoning: Explain mechanism (lane separation → smoother flow).

- Motive: “For commuters, this means shorter, more predictable journeys.”

Counter-view + Refutation

Acknowledge a strong objection, then disarm it with logic, evidence, or reframing.

- Counter-view: “Critics argue that bike lanes take space away from cars.”

- Refutation: “However, trials show that dedicated lanes reduce bottlenecks and improve average traffic speed. In practice, overall road capacity rises because movement is more efficient.”

Helpful signals

- While it is understandable that …, it remains the case that …

- Admittedly …; nevertheless …

- Some contend that …; yet this overlooks …

The Conclusion — Reconfirm and Call to Action

- Rephrase the thesis (freshly).

- Summarise the best two reasons.

- End with a clear action (“schools should…”, “the council ought to…”) or a forward-looking benefit.

Language That Persuades (Without Sounding Pushy)

Rhetorical tools

- Parallelism: “safer, cleaner, calmer streets.”

- Triples: “plan, practise, and present.”

- Contrasts: “not a cost, but an investment.”

- Rhetorical questions: “If we can cut waiting times, why wouldn’t we?”

- Metaphor (lightly): “a roadmap to fair funding.”

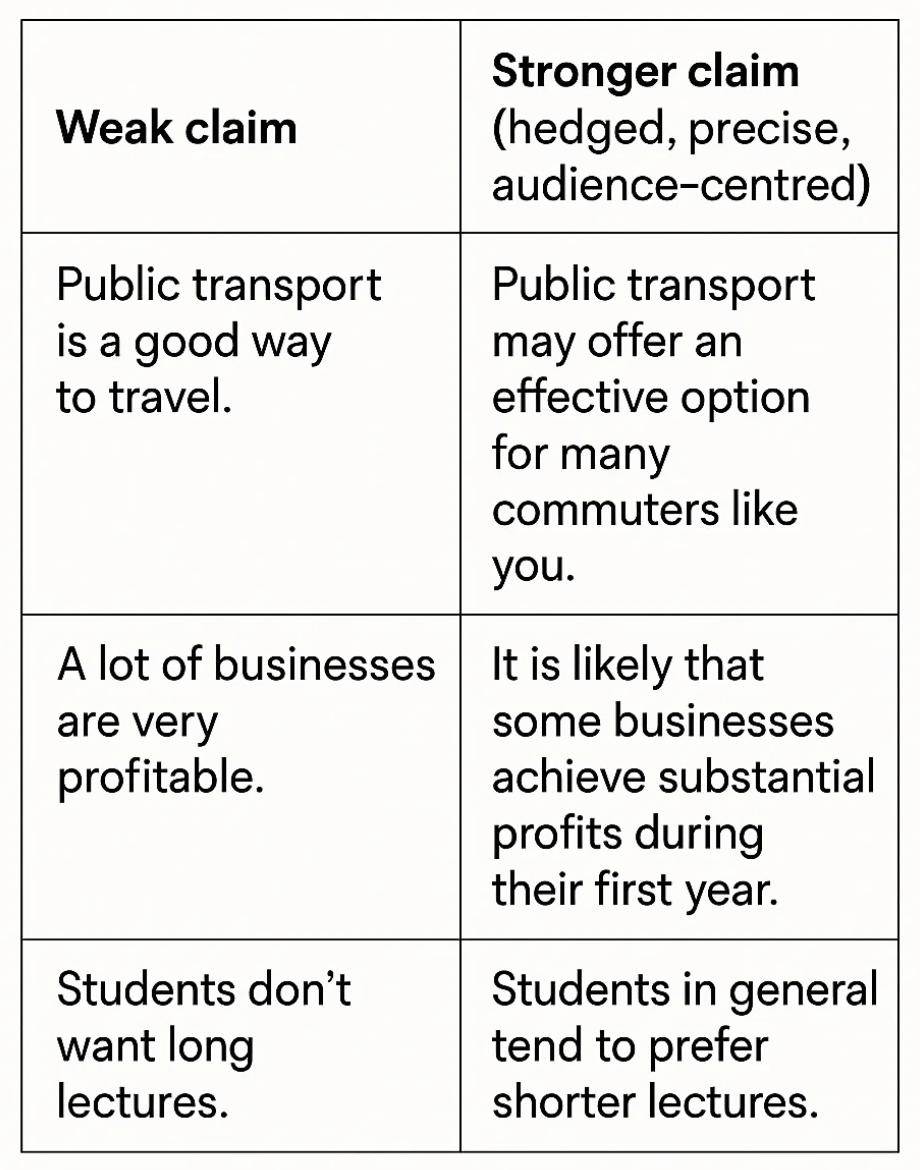

Hedging and precision

Avoid overstatement. Prefer may, can, tends to, is likely to to keep claims credible. Replace vague words (nice, good, bad, a lot) with precise terms (effective, harmful, substantial, numerous).

Full Example Persuasive Essay (≈ 360 words)

Prompt: Should local councils invest more in public libraries?

Introduction

When budgets are tight, libraries are often first in line for cuts. Yet a modern public library is more than shelves and silence; it is a community hub for learning, digital access, and social connection. This essay argues that councils should increase funding for public libraries because they expand opportunity, strengthen communities, and deliver excellent value for money.

Reason 1 — Opportunity

Firstly, libraries expand opportunity by providing free access to books, study spaces, and the internet. For pupils without quiet rooms at home or reliable broadband, the library can be the difference between falling behind and keeping pace. Targeted study clubs and homework help can improve attainment, particularly in disadvantaged areas.

Reason 2 — Community

Secondly, libraries build community. From baby-and-toddler reading groups to conversation clubs for new arrivals, they offer inclusive, low-cost activities that reduce isolation. In towns where high streets are struggling, libraries keep footfall steady and provide safe, welcoming spaces for all ages.

Reason 3 — Value for money

Thirdly, libraries represent exceptional value. A single membership unlocks thousands of books, e-books, audiobooks, and online courses. Compared with the cost of private subscriptions or remedial education, libraries save residents money while raising literacy and digital skills — benefits that spill over into the local economy.

Counter-view + refutation

Some argue that “everything is online now” and that physical spaces are unnecessary. Admittedly, digital resources are crucial; nevertheless, not everyone has devices, stable connections, or the skills to navigate complex information. Libraries bridge this digital divide by offering equipment, training, and expert staff who guide users to trustworthy sources.

Conclusion

In short, libraries unlock opportunity, weave communities together, and pay for themselves many times over in social value. Councils should increase funding and modernise services, with a modest investment for a literate, connected, and resilient town.

Quick Revision Checklist

- Clear, action-oriented thesis

- Three convincing reasons (each with evidence and motive)

- A fair counter-view plus refutation

- Audience-centred language and benefits

- Precise, hedged claims (no overstatement)

- Strong, memorable call to action

Conclusion

A persuasive essay succeeds when it understands its audience, balances logic with human appeal, and ends with a confident call to action. Use the PERM method, anticipate objections, and write with precision.

Explore more writing and grammar guides by clicking Next Lesson next to sharpen your academic style and confidence.

If you're unsue of some of the vocab in this lesson, check the Glossary below, then try the quiz underneath to test what you've learned.

Glossary Section

- Thesis (noun) — your main position in one clear sentence.

- Claim (noun) — a point you want the reader to accept.

- Evidence (noun) — data, examples, or sources supporting a claim.

- Reasoning (noun) — explanation linking evidence to the claim.

- Counter-view (noun) — an opposing opinion you must address.

- Refutation (noun) — your response showing why the counter-view is weaker.

- Rhetorical question (noun) — question asked for effect, not an answer.

- Parallelism (noun) — repeated grammatical structure for emphasis.

- Hedging (noun) — cautious wording to avoid over-generalisations.

- Call to action (noun) — instruction encouraging the reader to act.

Practise What You Learned

Q1 (MCQ): Which statement best defines a persuasive essay?

A) A neutral report on a topic

B) An essay aiming to convince the reader to accept a viewpoint or act

C) A story about a personal experience

D) A purely descriptive piece

Q2 (True/False): A persuasive essay should ignore opposing viewpoints to avoid confusing the reader.

Answer:

Q3 (Short answer): In the PERM method, what does “M” stand for and why is it powerful?

Answer:

Q4 (MCQ): Which is the strongest thesis?

A) “Libraries are nice to have.”

B) “Councils should increase funding for libraries because they expand opportunity, strengthen communities, and provide excellent value.”

C) “Libraries have books and computers.”

D) “People like libraries.”

Q5 (Short answer): Give an example of hedging language and explain its benefit.

Answer:

(Correct answers below.)

Answers:

Q1: B) An essay aiming to convince the reader to accept a viewpoint or act

Q2: False — it should present a counter-view and refute it.

Q3: Motive — it explains why the reader should care, increasing buy-in.

Q4: B) “Councils should increase funding for libraries because they expand opportunity, strengthen communities, and provide excellent value.”

Q5: may / can / tends to — keeps claims cautious and credible.

Join over 500+ learners

Join the community for free resources and other learning opportunities.

No spam — only valuable English learning content.