Introduction to Writing an Argumentative Essay (Step-by-Step)

Argumentative essay writing is one of the most useful academic skills you can learn. There are many real life situations where you might need these skills, such as preparing for school assignments, university assessments, or professional writing. The ability to present a clear position, support it with evidence, and respond to counter-arguments will make your writing persuasive and credible.

In this lesson I am going to explain exactly how to plan, write, and refine a high-quality argumentative essay. We’ll cover structure, language, examples, and common mistakes, and I've even got a full model essay at the end. Let's start with the basics:

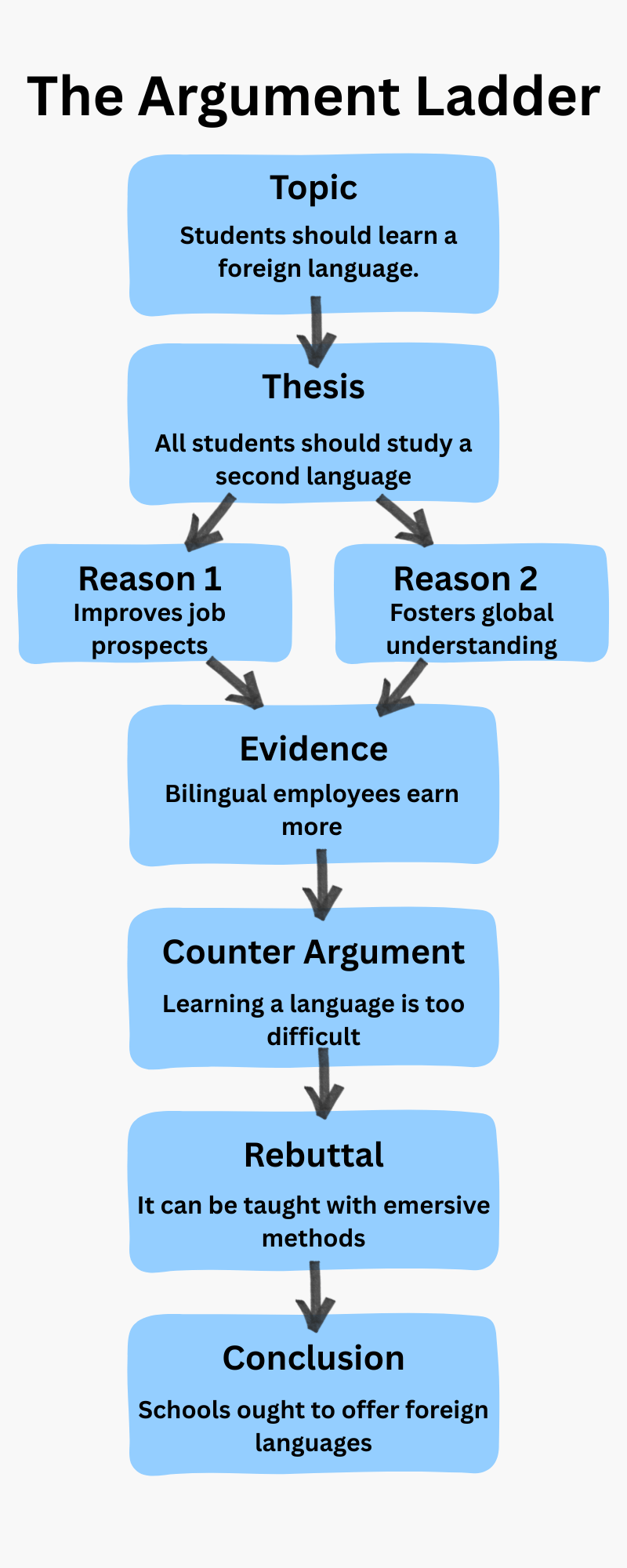

What is an argumentative essay?

An argumentative essay presents a clear claim (your main position) and supports it with reasons and evidence. Unlike a descriptive or narrative piece, the purpose here is to persuade a critical reader using logic, credible sources, and well-organised paragraphs. You also need to address opposing views and explain why your position still remains stronger.

Use our Dictionary

Don't know a word? Use our fun, free dictionary! Enter a word and you will see the meaning, pronunciation with an audio example, example sentence, and (hopefully) a great image to match!

Try for freeThe Standard Structure (and Why It Works)

The 5-paragraph framework (adaptable)

- Introduction — Hook the reader, give brief context, and state a precise thesis (your position).

- Body paragraph 1 — Your strongest reason with evidence and analysis.

- Body paragraph 2 — Your next strongest reason with evidence and analysis.

- Body paragraph 3 — Counter-argument + rebuttal (show awareness of other views and explain why your argument still stands).

- Conclusion — Restate the thesis (without repeating exact wording), summarise key points, and give a clear closing statement or implication.

Tip: At university level, you’ll often write more than five paragraphs. That’s fine, just keep the logic the same:

claim → evidence → analysis → counter-argument → reaffirmation.

Suggested word counts (for a 1,000–1,200-word essay)

- Introduction: 120–150 words

- Each body paragraph: 220–260 words

- Conclusion: 100–150 words

Planning That Saves Time

Pre-writing checklist

- Clarify the question

Underline task words (discuss, evaluate, argue), topic, and any limits (time period, population, context). - Choose a defendable thesis

Avoid vague claims (e.g., “Technology is good”). Use precise stance language:- “This essay argues that … because …”

- “It will be contended that … due to …”

- “The essay maintains that … on the grounds that …”

- Brainstorm reasons and evidence

Aim for 2–3 strong reasons. Map each one to data, examples, or citations you can explain. - Anticipate opposition

Note the most likely counter-point and think through a rebuttal (logical response, stronger data, different framing). - Draft a mini-outline

Create one line for each paragraph: topic sentence → evidence → analysis → link sentence.

Writing the Essay

The Introduction — Hook, Context, Thesis

- Hook: a statistic, brief story, question, or surprising claim.

- Context: 1–2 lines to define the debate.

- Thesis statement: one sentence that clearly states your position.

Example thesis frames

- “This essay argues that remote work increases productivity because it enables flexible scheduling, reduces commuting fatigue, and widens the talent pool.”

- “It will be contended that school uniforms should remain optional, as they limit personal expression and impose unnecessary cost.”

Body Paragraphs — PIE Method

Use the PIE structure:

- Point — topic sentence stating the paragraph’s main reason.

- Illustration — evidence: data, study, policy example, quotation, or real-world case.

- Explanation — analysis that links the evidence to your thesis and shows its significance.

Here's a model body paragraph template

- Point: “Firstly, flexible scheduling can improve focus and deep-work time.”

- Illustration: Provide a study, survey, or example (e.g., productivity metrics, absenteeism rates).

- Explanation: “This indicates that autonomy over working hours allows employees to align demanding tasks with their peak energy, thereby raising output quality.”

Counter-argument + Rebuttal

Strong essays acknowledge and answer opposing views. Place this as the final body paragraph or blend into earlier paragraphs.

- Counter-argument: “Some argue that remote work reduces collaboration.”

- Rebuttal: “While spontaneous in-person chats can be valuable, structured online communication and clear processes can offset this. In fact, teams that adopt shared documentation often report fewer misunderstandings.”

Useful transition language

- While it is true that … nevertheless …

- Admittedly … however …

- Critics may claim … yet this overlooks …

Conclusion — Close the Loop

- Reaffirm your thesis (fresh wording).

- Synthesise the key reasons (don’t add new evidence).

- Implication / recommendation: what should change, or what the reader should accept.

Language for Academic Tone

Hedging and Stance

- Hedging to avoid over-generalisations: may, tends to, appears to, is likely to.

- Stance for clarity: this essay argues/contends/maintains that…

- Cohesion: use signposting phrases — firstly, moreover, in contrast, consequently, therefore.

Avoid These Common Pitfalls

- Emotive language without evidence.

- Sweeping claims (“everyone knows…”, “always/never”).

- Paragraphs without topic sentences.

- Quotations without analysis (always explain relevance).

- No counter-argument (weakens credibility).

Full Model Argumentative Essay (approx. 340 words)

Essay question: Should universities continue to offer a significant proportion of lectures online after the pandemic?

Introduction

The rapid expansion of online teaching during the pandemic sparked a long-term debate about how universities should deliver courses. This essay argues that universities should maintain a substantial proportion of online lectures because the format widens access, supports flexible learning, and allows institutions to allocate in-person time to activities that benefit most from it.

Body paragraph 1

Firstly, online delivery widens access for students who commute long distances, work part-time, or have caring responsibilities. Recorded lectures allow learners to review complex material at their own pace, which can improve comprehension and note-taking. While not all students prefer asynchronous learning, the option reduces barriers and therefore supports participation.

Body paragraph 2

Secondly, moving standard content online frees up campus time for seminars, lab work, and small-group tutorials; the activities that benefit most from face-to-face interaction. When lectures are recorded, contact hours can be re-focused on discussion, problem-solving, and feedback, which tend to drive deeper learning. The result is a more efficient allocation of limited teaching hours.

Counter-argument + rebuttal

It is sometimes argued that online lectures reduce motivation and lead to procrastination. Admittedly, some students may delay watching recordings. Nevertheless, well-designed learning systems with clear weekly milestones, low-stakes quizzes, and attendance tracking for live Q&A sessions, can mitigate these risks. In practice, a blended model combines the flexibility of online materials with the accountability of in-person activities.

Conclusion

In summary, maintaining a significant proportion of online lectures is pedagogically sound and equitable. It broadens access, supports flexible study patterns, and enables universities to prioritise interactive teaching on campus. For these reasons, universities should continue to deliver lectures online while using face-to-face time strategically.

Quick Editing Checklist

- One clear thesis in the introduction

- Topic sentence at the start of each paragraph

- Evidence is cited or described and then explained

- At least one counter-argument + rebuttal

- Consistent academic tone and hedging

- Conclusion that reframes the thesis and states implications

Conclusion

Argumentative essays reward clear thinking and disciplined structure. If you plan your thesis, organise reasons and evidence, and address counter-arguments fairly, your writing will be convincing and professional.

Explore more writing and grammar guides next to strengthen your academic style and build confidence, or test your skills on the quiz below.

Glossary Section

- Thesis (noun) — the main claim or position your essay argues for.

- Claim (noun) — a statement you propose as true.

- Evidence (noun) — facts, data, examples, or quotations used to support a claim.

- Analysis (noun) — explanation of how the evidence proves the claim.

- Counter-argument (noun) — an opposing view that challenges your position.

- Rebuttal (noun) — your response showing why the counter-argument is weaker.

- Hedging (noun) — language that softens claims to stay cautious and accurate.

- Cohesion (noun) — how well ideas and paragraphs connect.

- Signposting (noun) — phrases that guide the reader through your structure.

- Citation (noun) — a reference that credits a source of information.

Practise What You Learned

Q1 (MCQ): What is the main purpose of an argumentative essay?

A) To entertain the reader

B) To describe a process

C) To persuade using reasons and evidence

D) To narrate a personal story

Q2 (True/False): You should avoid mentioning opposing views in an argumentative essay.

Answer:

Q3 (Short answer): What are the three parts of the PIE paragraph model?

Answer:

Q4 (MCQ): Which sentence best functions as a thesis?

A) “There are many views on recycling.”

B) “This essay argues that deposit-return schemes should be expanded because they increase recycling rates and reduce litter.”

C) “Recycling is important for the planet.”

D) “People should recycle more.”

Q5 (Short answer): Give one example of hedging language and explain why it’s useful.

Answer:

(Correct answers below.)

Answers:

Q1: C) To persuade using reasons and evidence

Q2: False — you should acknowledge and rebut them.

Q3: Point, Illustration (evidence), Explanation (analysis).

Q4: B) “This essay argues that deposit-return schemes should be expanded because they increase recycling rates and reduce litter.”

Q5: e.g., “may / tends to / appears to” — prevents over-generalisations and keeps claims cautious and credible.

Join over 500+ learners

Join the community for free resources and other learning opportunities.

No spam — only valuable English learning content.