How to Start Strong With Essay Introductions

Examiners decide how confident you sound within the first 6–8 lines. A focused, reader-friendly introduction sets the tone, clarifies your line of argument, and earns early credit for coherence.

In this lesson we've prepared, you’ll see practical essay introduction examples, proven patterns for how to write an essay introduction, and flexible essay starting sentences you can teach or use immediately, plus a printable worksheet.

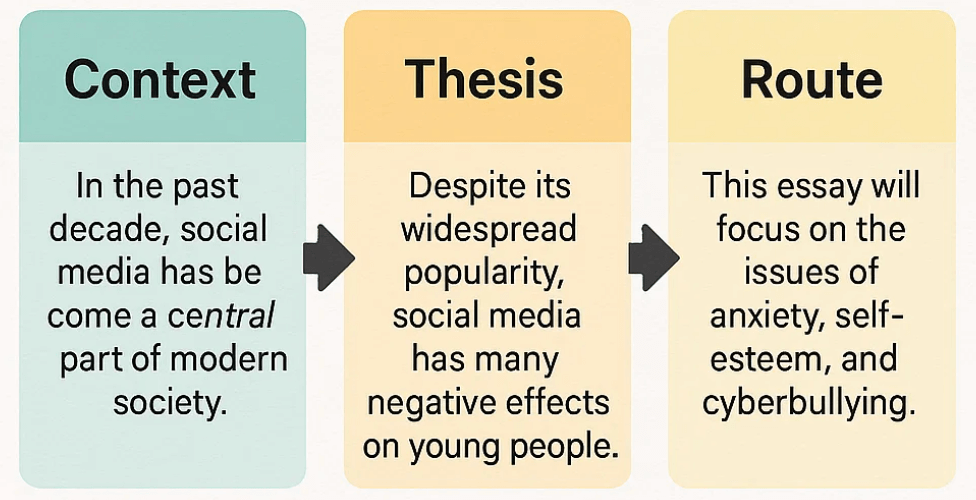

A strong introduction performs three jobs: it provides context, states a clear thesis, and maps the structure of the essay, useful for IELTS as well as working on school and university assignments.

Get those three right and the rest of your paragraphs will “click” into place. Let's get started.

Join over 500+ learners

Join the community for free resources and other learning opportunities.

No spam — only valuable English learning content.

What a strong introduction must do

- Establish context: Show the topic’s scope and any necessary definitions—briefly.

- Deliver a thesis: One sentence that states your main claim or answer.

- Preview the route: A hint of the essay’s organisation so the reader knows what to expect.

One sentence each is enough for most academic introductions: context → thesis → route.

The 3–Step Intro Formula (C–T–R)

- Context (1–2 sentences)

- Paraphrase the question or topic in neutral, specific terms.

- Narrow the scope (time/place/group) so it’s not too broad.

- Thesis (1 sentence)

- Take a stance or provide a direct answer. Avoid factual statements that nobody could disagree with.

- Route (1 sentence)

- Signal how the essay will develop (two key reasons, a compare/contrast path, causes then solutions, etc.).

Example (Argument/Opinion essay):

Context: “Urban congestion has intensified in many large cities over the past decade.”

Thesis: “This essay argues that cities should invest more in public transport than in new roads.”

Route: “It will show that transit upgrades reduce journey times more effectively and deliver wider environmental benefits.”

Essay introduction examples by task/purpose

A) Opinion/Argument (Agree/Disagree)

Prompt (short): Government funding: arts vs. sports.

Intro:

“Public spending choices shape the culture and health of communities. This essay argues that councils should prioritise the arts alongside sports, because creative industries fuel local jobs while public events build social cohesion. It will first explain the long-term economic benefits of cultural programmes, then consider how balanced investment supports well-being.”

Why it works: Tight context, clear stance, two-step route.

B) Discussion (Both Views + Your View)

Prompt (short): Remote work vs. office work.

Intro:

“Remote work offers flexibility and quiet focus, whereas office environments encourage mentoring and quick collaboration. While each model has strengths, this essay contends that a hybrid approach serves most organisations best, examining productivity and professional development before proposing a practical balance.”

Why it works: Both views are named neutrally; the thesis chooses a side; route previews criteria.

C) Advantages & Disadvantages (Evaluate)

Prompt (short): AI translation for language learners.

Intro:

“AI translation has rapidly become a study tool for learners worldwide. Although it accelerates reading comprehension, it can undermine independent vocabulary growth, so this essay evaluates the trade-offs and suggests guidelines for using translation responsibly.”

Why it works: Context, balanced thesis, evaluation route.

D) Problem–Solution

Prompt (short): Teen screen time and sleep.

Intro:

“Many teenagers now sleep less than the recommended eight hours. To address this, schools and parents should coordinate limits on late-night screen use and reinforce healthy routines, and this essay outlines practical steps for both groups.”

Why it works: Problem named; thesis proposes who should act; route indicates the structure.

E) Two-Part Question

Prompt (short): Why do fewer people read newspapers? How to reverse the trend?

Intro:

“Digital feeds deliver personalised headlines within minutes, drawing readers away from print. This essay first explains the shift towards mobile news and then proposes school-based media literacy and discounted e-subscriptions.”

Why it works: Direct response to both parts; concise route.

Essay starting sentences you can adapt (teacher-friendly stems)

- Context stems:

- “In recent years, [topic] has become a central issue in [place/sector].”

- “There is growing debate about [X], particularly regarding [Y vs. Z].”

- “For [group], decisions about [topic] carry significant consequences.”

- Thesis stems:

- “This essay argues that [claim] because [reason 1] and [reason 2].”

- “Although [counterpoint], [main claim] is more convincing since [reasons].”

- “This essay maintains that [position], as will be shown by [A] and [B].”

- Route stems:

- “It will first [criterion A], then [criterion B].”

- “The argument proceeds by [cause] and [consequence/solution].”

- “The discussion compares [X] and [Y] before reaching a judgement.”

Common errors—and quick fixes

- Overlong opening: Students write a mini-essay before stating the thesis.

Fix: Limit context to 1–2 sentences and move the thesis earlier. - No stance: The introduction summarises the issue but never answers it.

Fix: Add a decisive verb (should, outweighs, undermines, leads to). - Vague route: Reader can’t predict the structure.

Fix: Name the two reasons, the two sides, or the cause/solution path. - Copying the question: Simply repeats the prompt.

Fix: Paraphrase with synonyms and narrowed scope. - Over-hedging: Four cautious words in a row (might/could/perhaps/possibly).

Fix: Keep one hedge if needed; replace the rest with clear verbs.

How long should an introduction be?

For most academic tasks (including IELTS Writing Task 2), 3–5 sentences are sufficient: one for context, one for thesis, one for route, and optionally one more for a definition or nuance. Keep sentences 20–30 words where possible to maintain control.

Planning your introduction in 60–90 seconds

- Underline the task type (opinion, discussion, etc.).

- Draft your thesis first in one sentence.

- Write a single context sentence that paraphrases the question and narrows the scope.

- Add a route sentence naming your criteria or sequence.

- Read aloud once to cut filler.

Model intros (mini set you can reuse in class)

1) Opinion

“School meals influence pupils’ health and concentration. This essay argues that governments should subsidise nutritious lunches, first by showing the link between diet and learning, then by explaining how subsidies can be targeted fairly.”

2) Discussion

“Some educators prioritise examinations; others prefer coursework. While both generate useful evidence, this essay argues that mixed assessment is fairer, evaluating reliability and feedback quality.”

3) Advantages/Disadvantages

“Tourism can revitalise local economies but threaten ecosystems. This essay argues the benefits outweigh the risks where visitor numbers are managed, considering employment and environmental safeguards.”

4) Problem–Solution

“Plastic waste continues to rise in coastal cities. This essay proposes deposit-return schemes and municipal bans on the most harmful items, outlining funding mechanisms and enforcement.”

5) Two-Part Question

“Fewer commuters use buses during off-peak hours. This essay first examines why ridership has fallen and then suggests fare caps and real-time information to rebuild trust.”

Conclusion

A convincing introduction is short, purposeful, and predictable: context, thesis, route. Use the stems, practise timed drafting, and study the essay introduction examples above to sharpen your style. Once the first paragraph is in place, the rest of the essay flows.

Next step: Explore more Writing Skills guides and download the Introduction Builder worksheet for classroom or self-study.

Glossary

- introduction (n.) — the opening paragraph that sets context and position.

- thesis (n.) — one-sentence main claim or answer to the question.

- route (n.) — a brief map of how the essay will develop.

- stance (n.) — the writer’s position on the issue.

- paraphrase (v./n.) — express the same idea using different words.

- hedging (n.) — cautious language (e.g., might, could) that softens a claim.

- coherence (n.) — overall clarity and logical flow of ideas.

- task type (n.) — the essay purpose (opinion, discussion, advantages/disadvantages, problem–solution, two-part).

- evaluate (v.) — assess strengths and weaknesses to reach a judgement.

- criterion (n.) — a standard or measure used to structure your argument.

Practise What You Learned

Questions

- True/False: The introduction should normally include context, a thesis, and a route.

- Which sentence best functions as a thesis?

A. “There are many views on tourism.”

B. “Tourism should be limited in fragile ecosystems to prevent long-term damage.”

C. “Some countries rely on tourism for income.”

D. “This topic is very important today.” - In the 3–Step Intro Formula, the route does what?

A. States background facts.

B. Names the evidence in full detail.

C. Signals how the essay will be organised.

D. Repeats the thesis with synonyms. - Rewrite this weak context sentence so it narrows the scope:

“Technology has changed education.” - Draft a one-sentence thesis for: “Should fast fashion be taxed to reduce waste?”

(Answers below.)

Answers

- True.

- B. It is arguable and specific.

- C. It previews the structure (criteria or sequence).

- Sample: “Over the past five years, widespread laptop use in secondary schools has altered how pupils take notes and submit homework.”

- Sample: “Governments should impose a modest tax on fast fashion to curb clothing waste and fund textile recycling.”

Join over 500+ learners

Join the community for free resources and other learning opportunities.

No spam — only valuable English learning content.